On Folding Ground @ Night Café

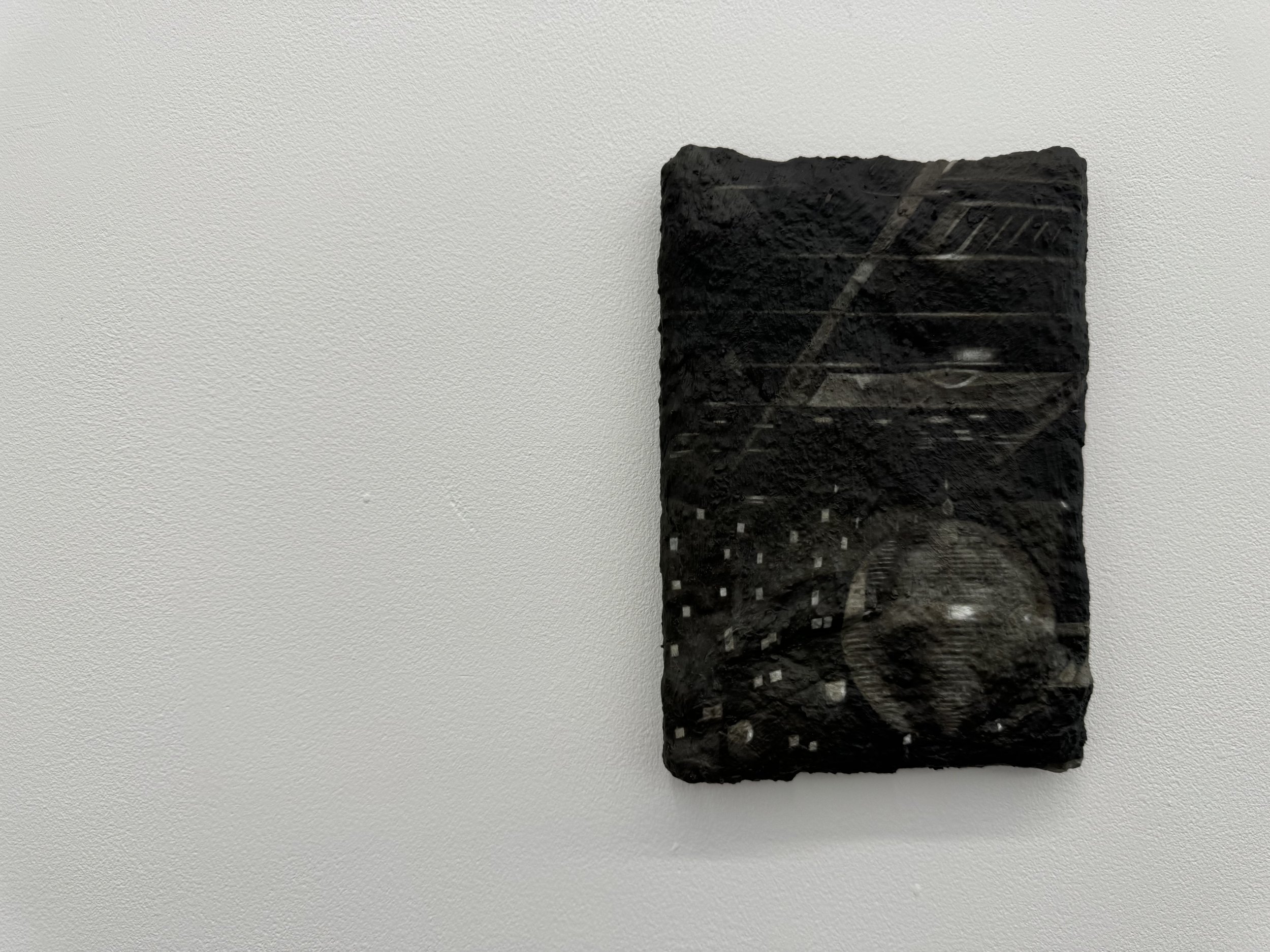

Art or artefact? That’s the question I ask on entering the gallery. Of course I know that Lucy Neish (@lucy_neish) is a painter, but her postcard sized works have so many textured contours of dried oil paint, caked-on so thick it looks like it might crumble off the edges, that it’s easy to assume her works could be trace fossils on slabs of excavated rock. Their dirty grey and dusty colours add further fuel to my imagined fantasy that she didn’t actually paint these, but simply dug them up.

Of course, you can’t actually tell that when you walk in the door. Quite frankly, from more than a few metres away these just look like dark rectangles. At 12x17 centimetres you’re forced to get quite close before you can even begin to appreciate them, and getting quite close fundamentally changes how you engage with a work. You lean in. You become focussed. You become mindful of subtle details, such as tiny brushstrokes that you’d never notice in a larger painting when standing a meter away.

In Niesh’s work those brushstrokes often have shadows. Literally. Her process is an additive one, layering and layering and layering the oils. Unevenly. Possibly erratically. Bumps and ridges appear in the canvas, over which the image casually flows like water over a rock. Some layered areas have a direct correlation to the visual peaks and troughs of the image, accentuating their highlights and shadows in a miniature relief. I spent a lot of time looking at her rabbit’s ear, wondering whether or not those wayward white hairs were painted or actually there.

Niesh’s paintings are a slow, methodical process of accumulation. Adding shape, texture and intrigue to imagery that likely wouldn’t draw your attention otherwise. Whereas Rebecca Halliwell Sutton (@studemood) works in reverse. She starts with an item, whether a small imaged plate or a large sheet of aluminium, and slowly works it away by chipping, hammering and even using chemicals to dissolve it. It’s not the same intentioned removal as, say, sculpting from a block of stone, but she is still removing extraneous bits in order to end up with something completely different and new, but something that arguably always existed. The task of the artist is to figure out which process is the best way to reveal those hidden, core elements of beauty.

I’m told by the gallery that Halliwell Sutton liked the way that sunlight streaked across a large sheet of aluminium that she had in her studio. She traced it as a template against which hammer marks were methodically made, slowly working to distress, curve and eventually puncture the work into the form you see balanced on a steel base. It’s not attached. It wobbles, and it might possibly get blown to the floor if a giant gust of wind were to somehow find its way through the gallery door. It sits in the centre of the gallery, like a piece of industrial salvage waiting to be repurposed. Does the work actually mean anything or does it just look cool? Does it matter?

Plan your visit

‘On Folding Ground’ runs until 11 October.

Visit nightcafe.gallery and follow @nightcafegallery on Instagram for more info about the venue.

PLUS…

Check the What’s On page so you don’t miss any other great shows closing soon.

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. (It’s FREE!)