Electric Dreams: Art and Technology Before the Internet

In the 1985 movie ‘Back to the Future’ Christopher Lloyd plays a mad scientist that cobbles together random household gadgets and consumer technology. By combining parts that were never meant to interact, and using them to do things they were never intended to do, he made something fantastic. “You built a time machine… out of a DeLorean?!” exclaims his co-star Michael J. Fox. That quote was running through my head throughout Electric Dreams, filled with whimsical artistic creations and mesmerising displays of creativity that came about from artists doing pretty much what Doc Brown did in the movie: experiment without boundaries to find out what unexpected things new technologies could do.

Coincidentally, the scope of the show loosely aligns with the timelines portrayed in the movie. It begins in the 1950s, a decade of scientific and technological advancements that would lead to the space race, and ends in the early 1990s when the internet was just starting to emerge as a widely adopted public utility. It was a distinctly unique half century because unlike the Industrial Revolution this era made rapid technological advances directly accessible to the public. That’s something that the artists in this show clearly embraced with a sense of whimsy and wonder.

The opening room contains video art that a modern primary school child with an iPad would consider quaint. It’s presented alongside photos of Atsuko Tanaka’s Electric Dress, a wearable artwork made from light bulbs and incandescent tubes. “It was uncomfortably hot, heavy, and in the event of a short circuit, potentially deadly.” These two works set that stage for the charm offensive that repeats throughout the show.

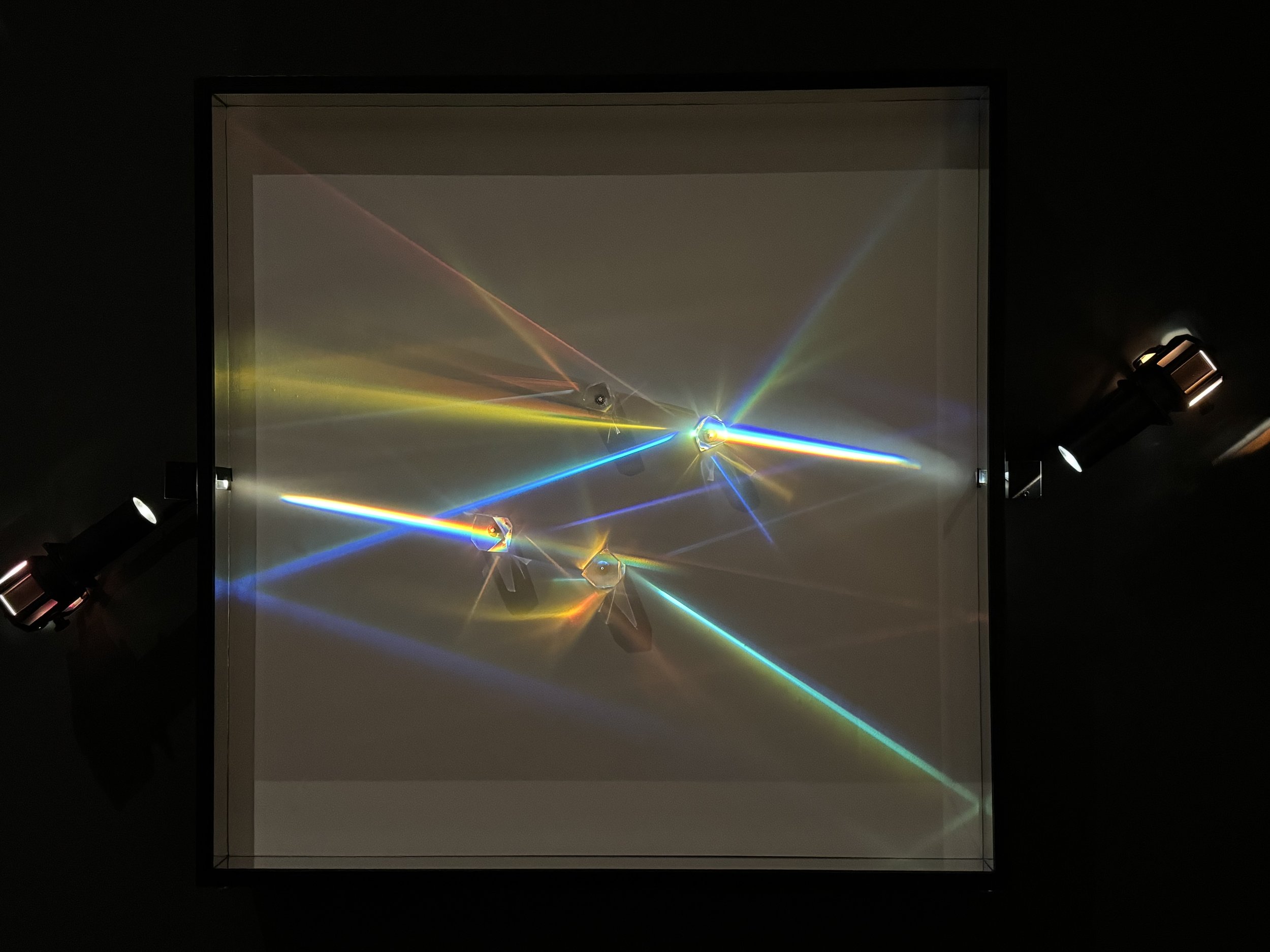

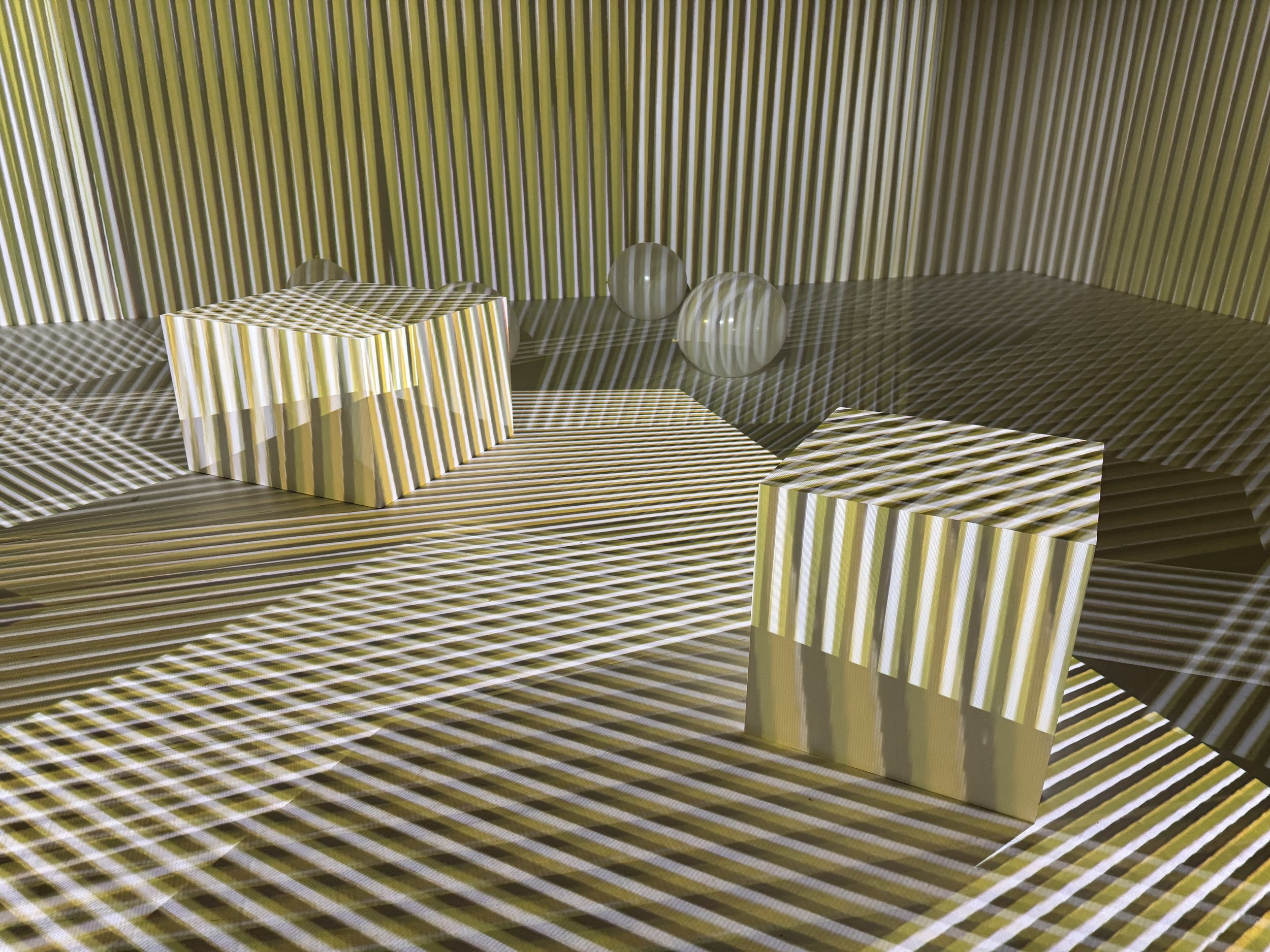

Most of the works look like something you could make over a long weekend in your grandfather’s shed. Many are kinetic, and being able to see how they work and are constructed gives them a tactile warmth. That applies to both small works — like David Medalla’s sand machine in which a motor hidden inside a log spins a beaded swing, creating drag lines in sand — as well as larger, whole-room experiences. Otto Piene’s ‘Light Room (Jena)’ and Carlos Cruz-Diez’s ‘Chromointerferent Environment’ are early examples of immersive environments that fundamentally aren’t that different than modern examples, except theirs were made with slide projectors, motors and incandescent lights. As a result they feel infinitely more human than the awe-inspiring but somewhat sterile Ultra HD screen experience you’ll find at Tottenham Court Road.

From the static works that make clever use of patterns to trick your eyes into seeing motion that isn’t really there, to the works that actually animate sound and light, much of this show inspired me to think about what might be possible with the odds and sods lying around my house. Those old enough or at least familiar with the various technologies used will understand just how cutting-edge many of these artworks were at the time they were created. Unfortunately, given the age and fragile state many are in, some of the mechanical works are only activated once or twice an hour. Understandable, but frustrating.

Another minor issue is that the show starts to lag as it enters the digital age, when most of the advancements that enabled the things you’ll see were no longer mechanical. They were made with code. There probably aren’t that many people left who know how to program FORTRAN, so it’s harder to appreciate just how much effort it took to create some of the primitive looking computer graphics. The examples you’ll see were mind-blowing at the time, but it’s still a hard sell to get modern audiences engaged with Harold Cohen’s simplistic and static machine-generated drawings after they’ve spent ten minutes zoning out to the kinetic, psychedelic 60s light works from Italian Arte Programmata in Room 6.

Yet when viewed through the lens of the digital age that we now live in you’ll be amazed by how many modern concepts you’ll see in antiquated, dated packaging. This isn’t a show about futuristic sci-fi concepts that make you wonder what could be. It’s a show about what is, through the lens of what was. Everything naturally fits in to technological family tree of today’s world. The experience is like going to a natural history museum, where you can see the evolutionary changes that clearly explain how the world you inhabit came to be. Except these works aren’t dusty old bones. They still shimmy, shake and spin and you’re definitely gonna wanna dance along with them.

Plan your visit

‘Electric Dreams’ runs until 01 June 2025.

Tickets from £22 adult / discounts and child prices available

Visit tate.org.uk and follow @tate on Instagram for more info about the venue.

PLUS…

Check the What’s On page so you don’t miss any other great shows closing soon.

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. (It’s FREE!)