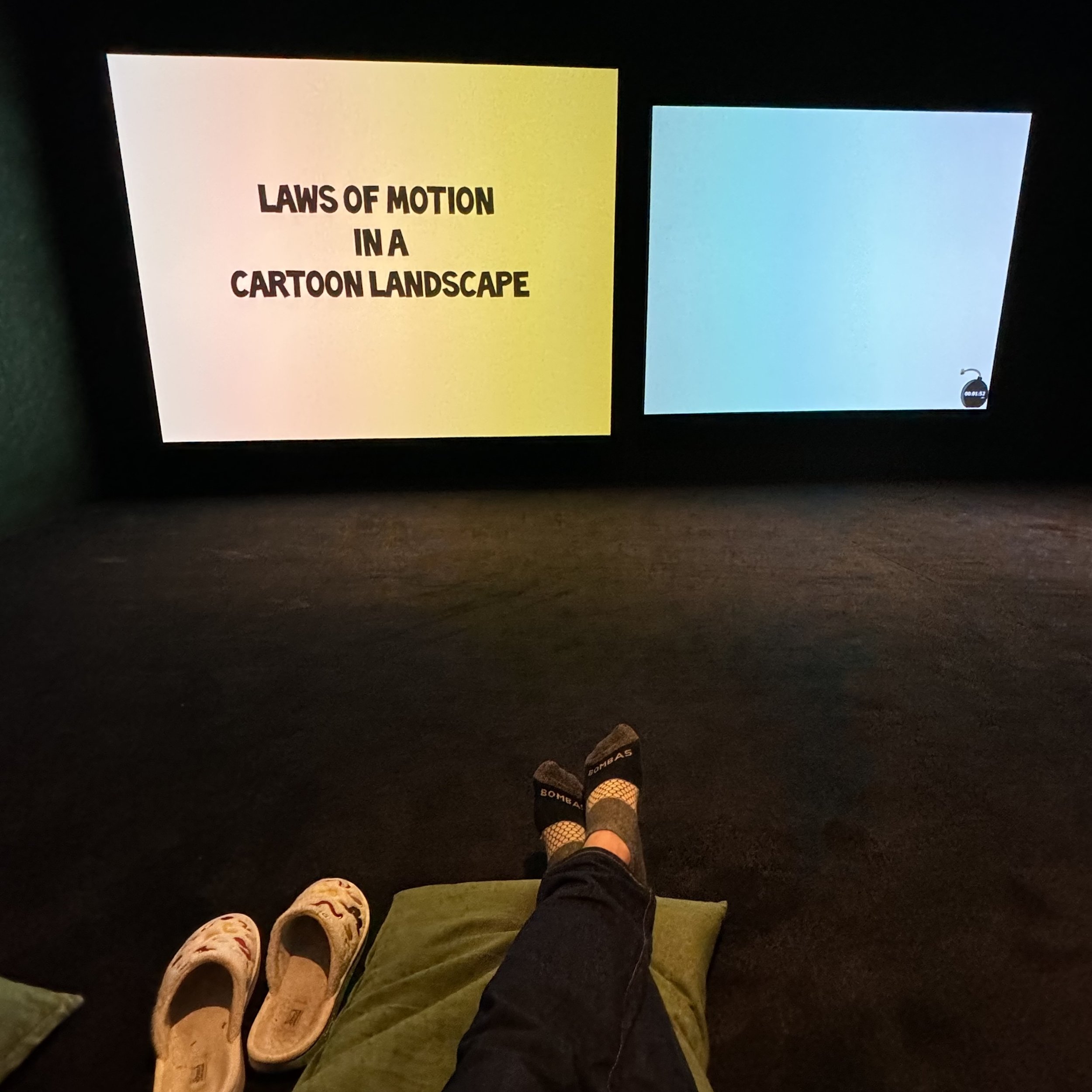

Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape

What ever happened to good old-fashioned casual escapism? Once upon a time one story was enough. You’d eagerly disappear into a movie or book for a few hours then return to the real world. Maybe the occasional sequel would pique your attention, but that wasn’t always necessary. Nowadays the world can’t seem to live without endless sequels, prequels, reboots and companion TV shows. And that’s just the visual output around which games, books, comics, toys and other merchandisable things elevate what was once a single story into a pervasive and constantly expanding entity.

Modern escapism goes much, much deeper than a few hours of distraction but understanding why people are no longer satisfied to let a story end after a single instance is a matter for the sociologists. What is obviously clear to me, though, is that audiences no longer want to be passive. They want to be fully invested with their favourite characters and concepts, and frequently take the initiative to extend those stories themselves by expanding and defining, to incredibly deep levels of detail, entire worlds into which they can escape for extended periods of time.

It’s why people learn to speak Klingon. It’s why there are countless YouTube videos explaining how to make your own lightsaber. It’s why Britain's Harry Potter movie tour has generated more than $1 billion of revenue since it opened 12 years ago. It’s called Worldbuilding and it’s something that I couldn’t stop thinking about when I recently viewed Andy Holden’s 2016 film ‘Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape’.

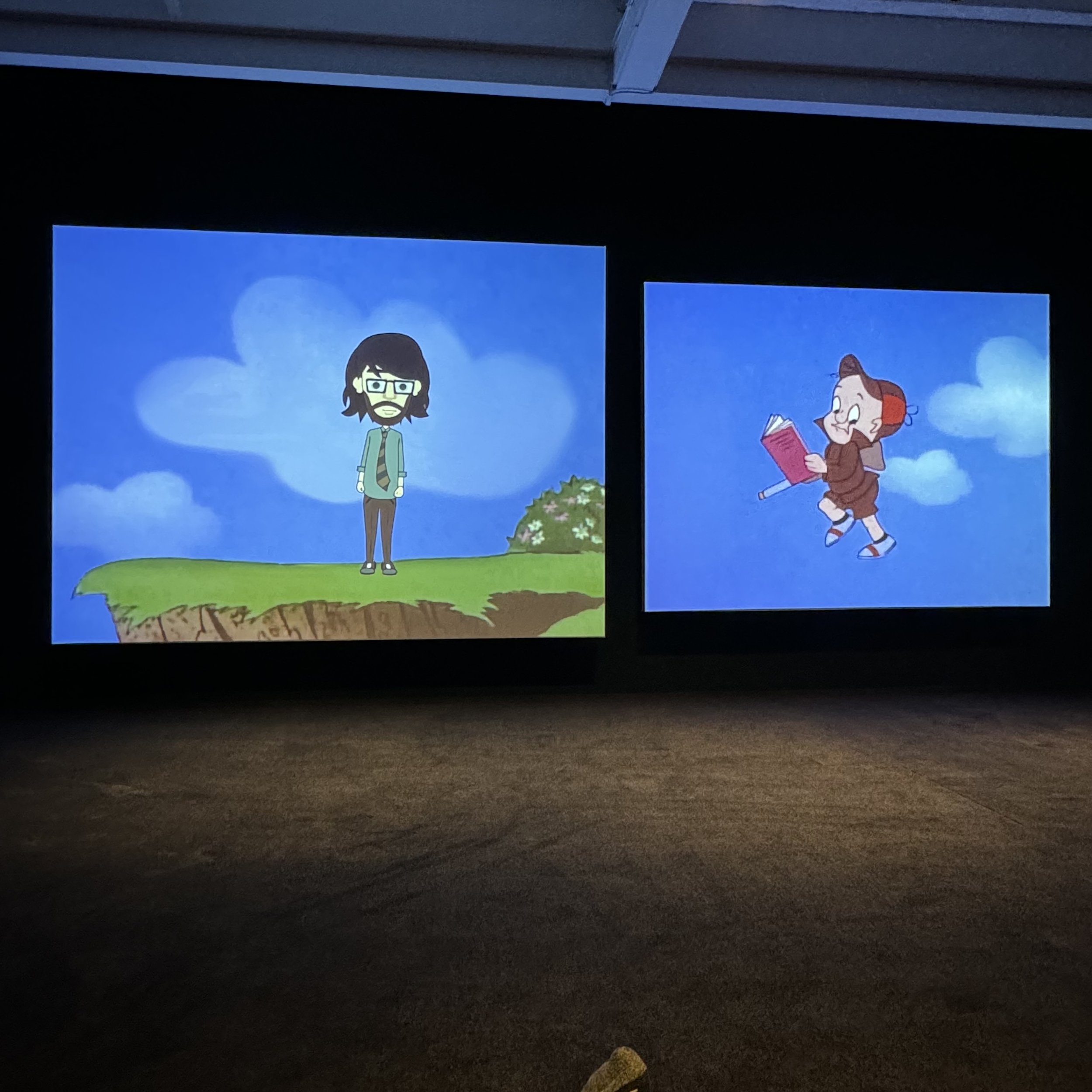

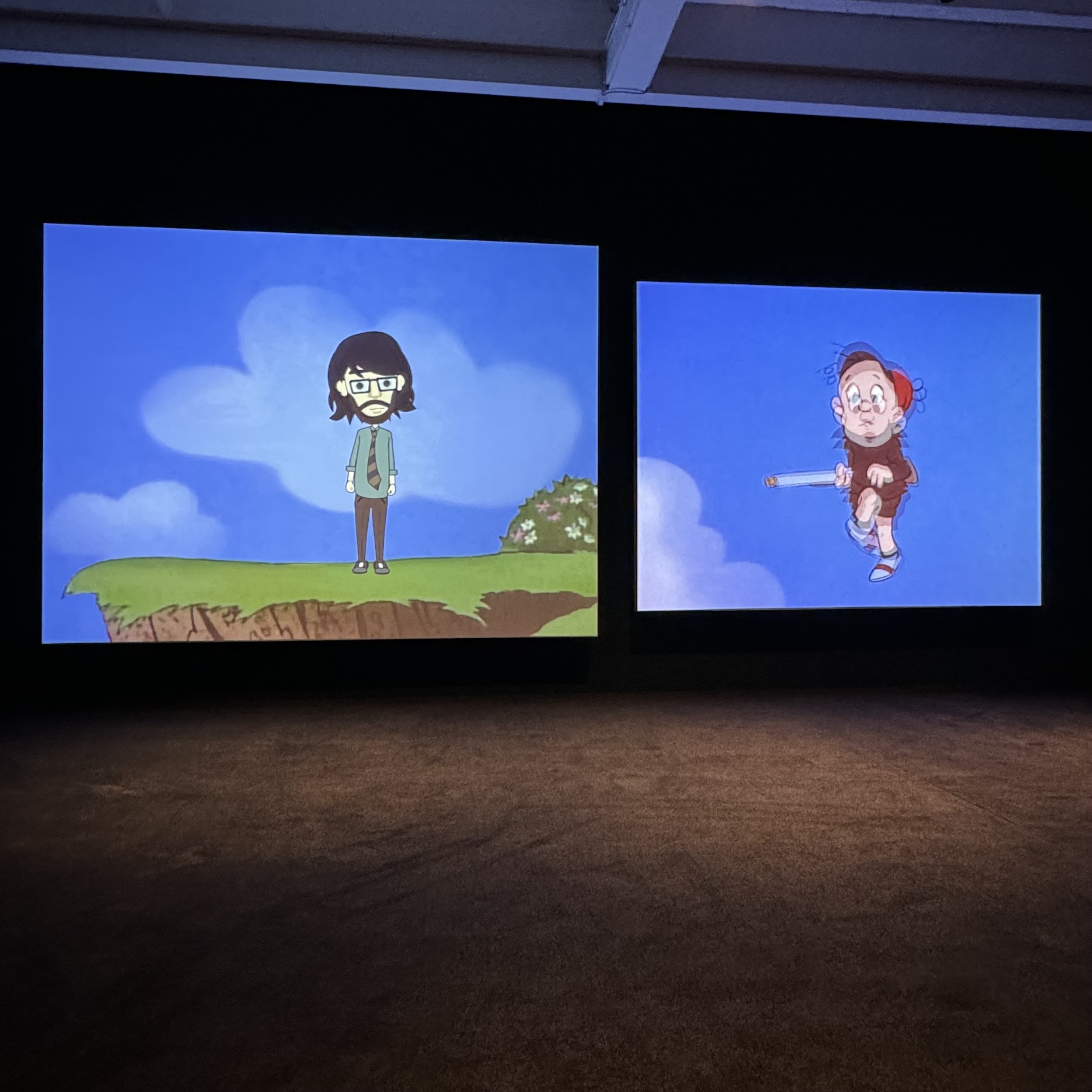

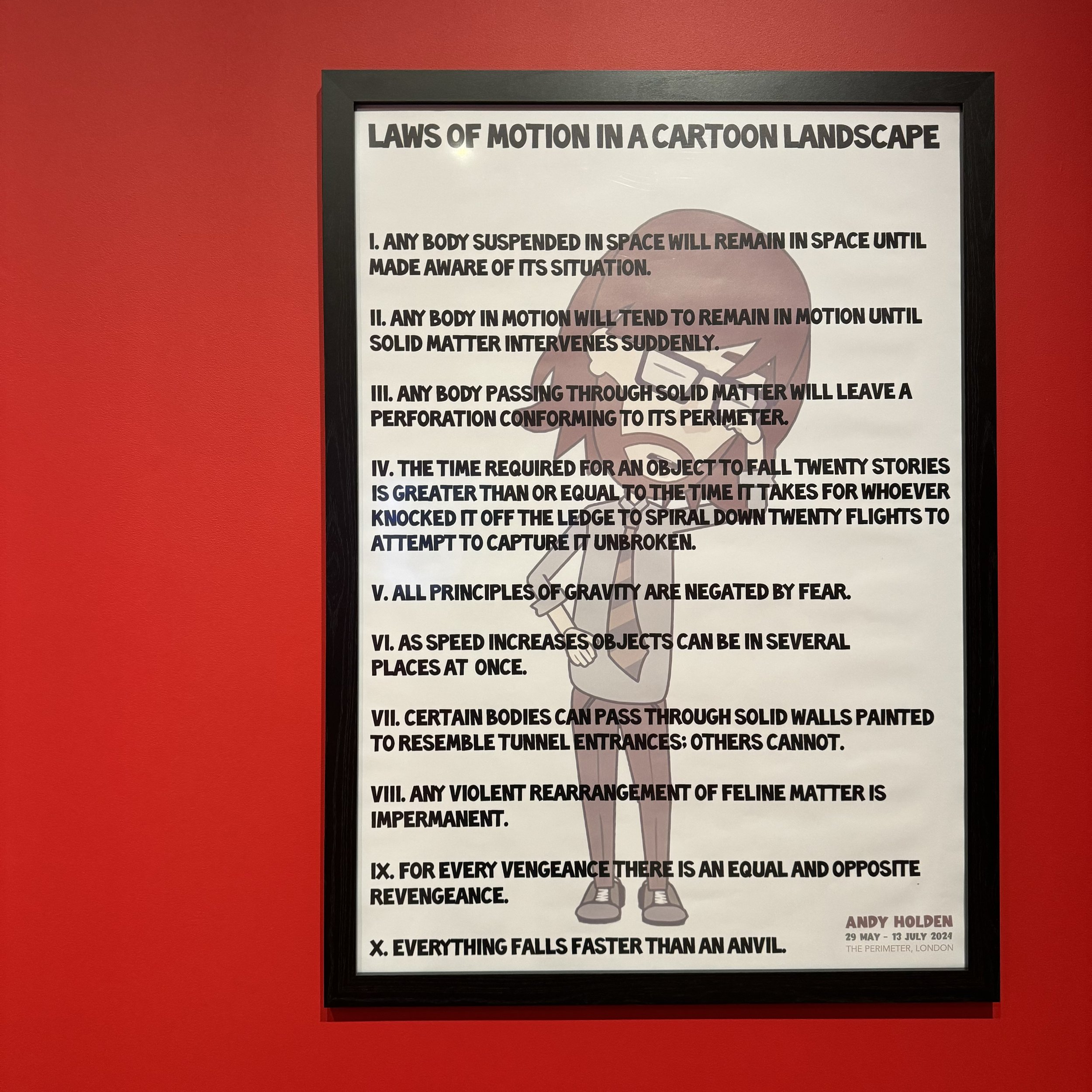

To briefly explain the film, it’s a proposition of 10 Laws based on recurring themes and actions that Andy observed in classic cartoons made between the mid-1920s and early 1960s. For example, Law 1 states: “Any body suspended in space will remain in space until made aware of the situation.” A common visual gag shows a character being chased off the edge a cliff except they float in mid-air, continuing to run as if they were actually on land. It is only once they are made aware of the fact that they are not on hard ground that gravity finally intervenes, and the character inevitably falls to a splat.

You don’t need to be well versed with Looney Tunes or Hanna-Barbera to appreciate the humour in Holden’s film, but those who grew up watching Saturday morning cartoons will inevitably be able to guess what’s coming. Holden’s Laws, however, are not merely snarky observations. The film commences with a whirlwind history tour of animation technology, some basic Newtonian scientific explanations and a few bold statements like “the cartoon landscape predicted surrealism”. Much like a PhD thesis, Holden’s entire conceit is meticulously researched and backed up with credible references. None other than Walt Disney himself appears in archival footage, providing explanations that validate some of the Laws.

Holden goes to such an effort to treat these as real theory that I couldn’t help but get stuck in scientific mode, trying to pick apart holes in his logic. For instance:

Law 3 and Law 7 offer contradictory explanations for how bodies interact with solid matter. Or maybe one is just a loophole?

Law 9 was left completely unexplained. It states “For every vengeance there is an equal and opposite revengeance.” I suspect the clips for that one would have kept me laughing for hours.

Holden’s window of observation seems to assume the Cartoon Landscape was frozen in time around the mid-60s. There’s scant attempt to examine modern age cartoons to verify if the Laws are universal, probably due to limited time and copyright frustrations.

I got swept up analysing Holden’s analysis because he himself is not merely indulging in a mild fascination with cartoons. He’s obsessively picking them apart, meticulously studying their patterns and rhythms, calling our attention to what he perceives as proof of a previously unwritten set of laws that govern the animated world. In many ways Holden’s modest film is no different than Wookieepedia — the Star Wars encyclopaedia that had 193,196 pages of ridiculously comprehensive fan-created content at the time I wrote this article.

Holden’s art has “often been described as balancing an ironic sensibility with a deep sincerity” and that rings true with this work. It’s hard not to laugh along, but the Laws in his film are too thoroughly thought out to be considered mere satire. There’s a strong argument to be made that Holden’s film is not even a work of art at all, but a product of the times we are living in. By mirroring current obsessions with Worldbuilding whilst very much falling into that trap himself, Holden has created what might be one of the most acute statements about modern entertainment audiences that you’re likely to encounter.

Plan your visit

‘Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape’ was showing from 30 May - 13 July 2024. The photos in this story are from that exhibition.

Visit theperimeter.co.uk and follow @theperimeterlondon on Instagram for more info about the venue.

Visit andyholdenartist.com and follow @andyholdenphotos on Instagram for more info about the artist.

PLUS…

Check the What’s On page so you don’t miss any other great shows closing soon.

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. (It’s FREE!)