Noah Davis @ Barbican Art Gallery

Noah Davis died young. The American artist was only thirty-two when a rare form of cancer claimed his life. He left behind a wife, a young son, and a prolific body of ~400 works of art made in the eight years of his practice. The Barbican show is the first institutional survey of the artist and it’s not just his accomplished canvasses that warranted the recognition, but his generous artistic spirit, which drove him to paint not to seek fame but to bring art and representation to those for whom artistic expression is often denied or forgotten.

As you explore the show it becomes easy to forget that Davis was so young and had such a short career. The opening room, featuring his earliest paintings, shows us that Davis started as strong as he meant to go on. His body of work is fundamentally portraiture, but not of any particular person. Davis’ aim was to portray the Black experience and he was steadfast in his determination to swerve away from the stereotypes and tropes often expected of black artists. His primarily did this via compositions based on found, amateur imagery. He’d spend weekends rummaging through flea markets for vintage photographs and family albums, he browsed internet photo sharing sites, and in one noted series of works he painted directly from photos his mother took when she was a teenager.

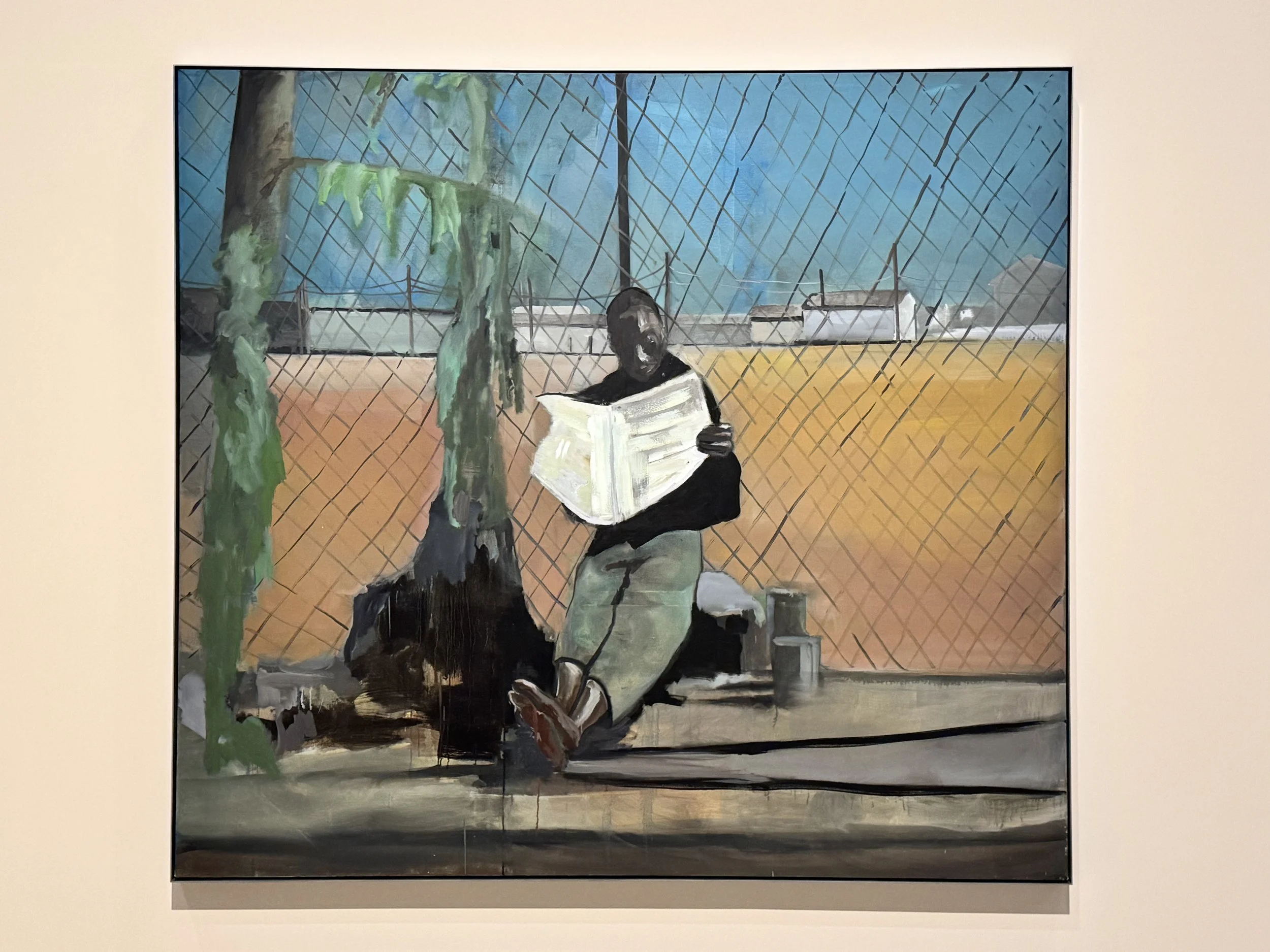

There’s something touching about Davis immortalising these once personal memories that had become disconnected from their source. Unknown to Davis, the figures retain their anonymity in his works. Faces are rarely seem. Signifiers of time and place have been removed. Expressions and emotions can only be inferred. The elements Davis retained and committed to canvas are almost shockingly banal. A man reading a newspaper. People standing in a doorway. Young women resting on a sofa. Basic, everyday things that everyday people do, regardless of colour. Davis said he wanted to “take these anonymous moments and make them permanent. I wanted Black people to be normal. We are normal, right?”

Except Davis makes the normal extraordinary with a stylistic approach similar to the way soft lighting and a soft focus lens are frequently used in romantic films. Hard edges and harsh realities are smoothed away, resulting in scenes that have a dreamlike quality further enhanced by the fact that it’s practically impossible to root Davis’s works to a specific time or place. There is little, if anything, in the 1975 series to date those paintings to 1970s Chicago. His Pueblo del Rio and Congo paintings could easily be misinterpreted as having been from any urban city setting. In Davis’ hands, fashion, architecture and other traditional signifiers of era and location aren’t used as identifiers, but emotional triggers. Instead of mystery these anonymous scenes feel familiar, inviting and safe.

The other way Davis made the normal extraordinary was the tireless generosity he dedicated to the Underground Museum, an art institution he and his wife founded in a historically Black and Latinx neighbourhood in Los Angeles. Their vision was to bring culture and museum-quality art to a community that had no access to it, and the exhibition spaces, garden and lending library became a much loved and highly regarded cultural hub. John Legend and Solange Knowles launched albums there and just prior to his death Davis agreed a partnership with LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) to put on a series of shows that borrowed from their permanent collection.

Critically, however, not everything is a success. Davis repainted over his early experiments with abstract after they went unsold, leaving only one work as a sample. His ‘Savage Wilds’ paintings, a highly political series in which Davis painted freeze-framed scenes to call out derogatory portrayals of Black people on American daytime talk shows, are strong in concept but visually uninteresting. Alongside the ‘Seventy Works’ series of mixed-media studies he made to keep active during chemotherapy, the inclusion of Davis’ digressions from portraiture raise interesting questions regarding the shifts and changes his practice might have undergone had his life not been unexpectedly cut short. It’s a stark reminder underlined by the closing documentary video in which Davis appears, looking so incredibly youthful and babyfaced that it’s hard to believe he’s the same artist who painted the fifty works you just viewed.

Plan your visit

‘Noah Davis’ runs until 11 May 2025.

Tickets from £18 adult / discounts and concessions available / children under 14 free

Visit barbican.org.uk and follow @barbicancentre on Instagram for more info about the venue.

Visit Noah Davis Wikipedia page for more info about the artist.

PLUS…

Subscribe to the Weekly Newsletter. (It’s FREE!)